Chapter 5: The Palace of Nations: A Monument to Peace

The Palace of Nations owes its presence in Geneva to the American president Woodrow Wilson, who forcefully opposed Brussels as the League of Nations’ headquarters. It owes its right-bank location to the League’s fist secretary-general, the Englishman Sir Eric Drummond, who insisted on “the view of Mont Blanc”. It owes its situation on the Ariana hillside to the American oil baron John D. Rockefeller, who donated to the League a library too large for the lakeside plot initially set aside, which could not be extended due to the Scotswoman Alexandrina Barton’s refusal to sell her nearby property.

The Palace owes its utopian dimension to the twentieth –– or “American” –– century: it was to be a “palace” dedicated to cooperation between nations, free from the violent, imperialist hierarchies of the previous “European” century. It owes its faith in the timelessness of its mission to the early twenty-first century, which is currently expanding and renovating it. A survivor of both the “failure of Geneva”– as the League’s inability to avert war in 1939 was deemed –– and the later vicissitudes of the UN, it stands today as a monument to peace. Sufficient cause for a World Heritage listing, it would seem.

Moreover, the building itself reflects the upheavals that rocked the architectural world between the time of its conception and the present.

© DR, book by Jean-Claude Pallas; Histoire et Architecture du Palais des Nations; (1924-2001); United Nations, Geneva

The previous chapter describes the international competition of 1927, which contrasted the avant-garde ideas of Le Corbusier and Hannes Meyer with a more traditional, academic understanding of a “world palace”. Since the jury was unable to choose a clear winner among the 377 submissions, the League chose five diplomats –– the “Committee of Five” –– to select the one they judged most suitable among the nine first prizes. In late December 1927, the committee chose the French architect Henri-Paul Nénot (1853–1934) and his Genevan associate, Julien Flegenheimer (1880–1938). Since the two partners’ proposal was still far from perfect, the Committee of Five asked them to draw up new plans in collaboration with three other architects recognized by the competition: the Italian Carlo Broggi (1881–1968), the Frenchman Camille Lefèvre (1876–1946), and the Hungarian Joseph Vago (1877–1947). The palace thus has five authors, who were led by Nénot until his death, then by Broggi.

The architects were asked both to represent an idea –– peace –– and to supply a functional working environment for the new international institution. They had to simultaneously create a monument and lay out an office building. In his submission, Le Corbusier dismissed the request for a monument: ”This palace was for working and listening. We made a large office building and invented a new architectural form: a room for listening.”(1) But a monument was what the League had asked for; it wished to embody “the peaceful glory of the twentieth century”.(2) The five anointed architects shared this bias.

They were not consulted, however, about the League’s political decision to swap the 6.6-hectare site in Sécheron, purchased in 1926-27 for 2.7 million francs, for the 25-hectare Ariana park, at no extra cost. The new plot could comfortably accommodate the Rockefeller library. Gustave Revillod had donated his property to the city in 1890 on the condition that nothing ever be built on it and no trees cut down. The city agreed to override this clause and make the land available to the League, provided that Revillod’s descendants agreed. They all complied, with the exception of a great-niece, Hélène de Mandrot. A passionate connoisseur of architecture, she pledged her consent only if Le Corbusier and the four remaining first-prize winners were allowed to participate in the final project. Le Corbusier and the German architect Erich zu Putlitz duly sent in some sketches, but to no avail: none of their ideas found favour with the committee of diplomats. Helène de Mandrot relented nonetheless.

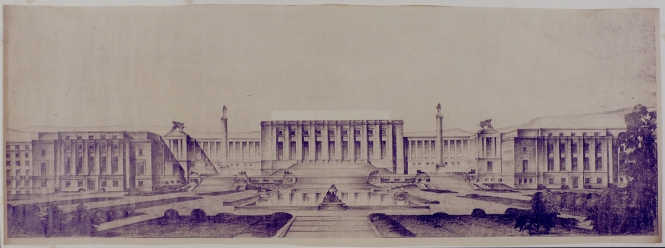

The chosen architects were asked to revise their plans to fit the League’s new site. They proposed a neoclassical structure on a monumental scale: a central building flanked by two horseshoe-shaped wings with severe, geometric façades devoid of decorative elements. The reinforced concrete structure would be covered in white stone from the Rhône valley and Italian travertine.

The final project proposed by the five chosen architects

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Work on the Palace –– the largest building site in Europe at the time –– lasted from 1929 to 1937, amid economic crisis and political disillusion. Work proceeded concurrently on every part of the building, each overseen by one of the five architects: the main building with the Assembly Hall and Salle des Pas Perdus, the two commission wings, the library, the Council Chamber, and the Secretariat. Completed in November 1933, the Assembly Hall was the grandest part of the complex, a temple identifiable by the ten columns without capitals lined up against its façade and the majestic stepped terraces in front, facing the lake, one of which has since been turned into a cafeteria.

In 1935, the final invoice was presented to the 16th Assembly of the League of Nations: 29.5 million francs, not counting the library, built thanks to an outside donation of 2.2 million francs, accepted by vote in 1927, which rose to 5.5 million by the end of construction.

As the historian Catherine Courtiau notes, the Palace’s ceremonial architecture was calculated to please all of the member states(3), whereas its interior design more clearly expressed the League’s aspirations to universality and rationality(4). Art nouveau, then art deco, had replaced the ornamental “decorative arts” of the empire and Biedermeyer periods. By the time the Palace of Nations was ready to be furnished and decorated, modernism was in full swing. Mass-produced light fixtures, furniture, and functional objects thus coexisted with luxurious carpets, woodwork, and wall decorations made to order by famous artists and craftsmen. The Palace’s interior embodies the minimalism and functionality of interwar design, two principles excluded from the building’s exterior. Today, these art deco furnishings are one of its most appealing features for visitors.

The Council Room in 1937, designed by René Prou, with the wall-paintings of José-Maria Sert

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Particularly noteworthy are the frescos by Catalan painter José Maria Sert in the Council Chamber, a gift from republican Spain; the Council’s private sitting room, known as the “salon français”, designed by the French decorator Jules Leleu; Alexandre Cingria’s stained-glass windows in the lobby and press room; and the building’s many period fittings, such as the light sconces in the hallways, the radiator grills, and the window drapes (5).

The Assembly Room, in 1937. Left and right, under the tribune, the two winged genii by Hubert Yencesse

© Charles-Edouard Boesch / Bibliothèque de Genève

Room II, former private room for the League of Nations’s Council, called «the French room », by Jules Leleu. The big engraved glass panel is by Anatole Kasskoff

© United Nations Archives at Geneva. In L'illustration

Room VI, private room for the delegates. The paintings by Karl Hügin and the panelling have been donated by Switzerland

© DR, book by Jean-Claude Pallas; Histoire et Architecture du Palais des Nations; (1924-2001); United Nations, Geneva

The Waiting Hall with its view on the lake and the Alps trough nine bay windows. Swedish marbles and monumental lamps by Jean Perzel’s workshop in Paris

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

“It’s huge, huge,” exclaims the character Adrien Deume in Albert Cohen’s novel Belle du Seigneur. “One thousand seven hundred doors, just imagine, each painted with four coats of paint for the most perfect white […] Not to mention the one thousand nine hundred radiators, twenty-three thousand square meters of linoleum, two hundred and twelve thousand kilometres of electric wire, one thousand five hundred faucets, fifty-seven hydrants, one hundred and seventy-five fire extinguishers - it’s really quite something!”

Yet it was still not enough. By 1946, when the UN replaced the League and chose to establish its European headquarters in Geneva, more space was urgently needed. In 1949, to house the UN system’s new technical organizations for health (WHO), telecommunications (ITU), and the weather (WMO), the Palace’s administrators considered building a 100-meter-tall tower, designed by the Frenchman Jacques Carlu. However, the Swiss architectural morality police promptly quashed the idea. Instead, the UN opted for a modest annex –– a “crushed tower” –– in the courtyard of the Secretariat complemented by a vertical extension of one of the existing buildings, neither of which altered the Palace’s academic style or original outline. The ITU, WMO, and WHO eventually moved into their own headquarters outside the Ariana.

The Palais, at the end of the1950s, after the first modest enlargment

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Though the idea of grouping all of the UN organizations in a central site made sense from a cost-sharing point of view, it was abandoned in the face of a tacit ban on high-rises. Besides, why crowd together when Geneva offered plenty of nearby space? The vague, somewhat haphazard layout of the “international quarter” — evolving as it did according to emerging needs, often in a hurry and with no fixed plan — can be traced back to these crucial post-war years. Geneva and the UN’s respective approaches to planning were not easily reconciled, and their decision processes even less so.

Moving the technical organizations away from the Ariana did not fully resolve the problem, however, as they still used meeting rooms at the Palace for large conferences. By 1964, when the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) was created to guide the process of decolonization, inadequate office space and facilities had become a serious issue. Argentina offered to host the new organization. A building committee formed in 1956 proposed several options for enlarging the Palace, which never amounted to anything. The crisis came to a head.

Finally, in 1966, the UN chose five architects to design and build an extension. The Italian Pier Luigi Nervi (1891–1979) and the Scotsman Basil Spence (1907–1976) would draw up the plans, while construction would be overseen by the Frenchman Eugène Beaudoin and his Genevan partners, Arthur Lozeron (1905–1970), André Gaillard (1921–2010), and François Bouvier (born 1928). The aim was to extend the Palace without transforming it, renewing its architectural language while preserving the spirit and harmony of the existing complex. “We shall build in the style of 1970, not 1935,” said Georges Palthey, the assistant director-general of the UN at the time (6).

After two years of proposals and counter-proposals, the two old masters, Eugène Beaudoin and Basil Spence (who became close friends in the process), finalized plans for a seven-storey office block next to the library, in line with the Secretariat. The simple, regular sobriety of its façade was set off by horizontal lines of light-coloured Tuscan travertine reminiscent of the Palace’s stone facing. A squat, three-storey structure next to the extension facing the lake accommodated ten conference rooms, including three large rotundas.

The new building. In front, the conference rooms

© Matthias Thomman, book by Jean-Claude Pallas; Histoire et Architecture du Palais des Nations; (1924-2001); United Nations, Geneva

The inauguration took place in 1973 in an atmosphere of general satisfaction. The new building would increase the workspace available to the UN by 65 per cent. But the initial budget of 54 million in 1966 had ballooned to 124 million by the end of construction. Switzerland provided funding of 4 million francs and a 56 million franc loan at three per cent interest.

In a recent study, Franz Graf and Giulia Marino of the EPFL judge the extension as of “exceptional value” and praise its beautifully executed conference rooms as “total works of art” of 1970s architecture (7).

Room XX, renamed Human Rights and Alliance of Civilisation Room, with its ceiling by Miquel Barceló, a gift from Spain

© Agusti y Antonia Torres / ONUART

In 2015, there was no protest when the UN published its plan for renovating the Ariana complex, which will involve dismantling the office block’s top four floors and replacing them with a new structure partly buried into the hillside.

Surrounded by splendid parkland, the Palace is now a favourite of the public and a popular tourist attraction. It helps raise Geneva’s visibility, which is why the Swiss government contributes so generously to its maintenance and renovation.

Yet the structure is unloved by architects: they side with Le Corbusier, whether they admire him or not, seeing in him a man of the present, like them, who waged battle with the past - and lost.

The whole Palais in 2016

© UN Photo / Jean Marc Ferré

(1) Letter from Le Corbusier to à Karl Moser, Paris, 30 January 1927.

(2) Programme du concours de 1926.

(3) Genève 1927, Concours pour le Palais des Nations, Institut d’architecture, 1995, pp.15-20.

(4) Catherine Courtiau, “Le Palais des Nations à Genève", Architecture en Suisse, vol. 56. 2005.

(5) Jean-Claude Pallas describes these works of art in his 2001 study of the Palace of Nations’s construction.

(6) Quoted by Franz Graf and Giulia Martino in Le siège de l’ONU à Genève, L’agrandissement du Palais des Nations, Etude patrimoniale, Laboratoire des Techniques et de la Sauvegarde de l’Architecture Moderne, Ecole Polytechnique fédérale, Lausanne, June 2005.

(7) Ibid.