Chapter 1: Sharing the beauty of Geneva

Competing with Brussels to host the headquarters of the League of Nations after the First World War, Geneva played one of its strongest cards: the romantic beauty of its lakeside setting, facing Mont Blanc. Only the best would do for the Council of the League of Nations. The people of Geneva complied, though not without a tinge of regret. This first article describes the reasons and circumstances leading to the establishment of the international quarter in the district it occupies today.

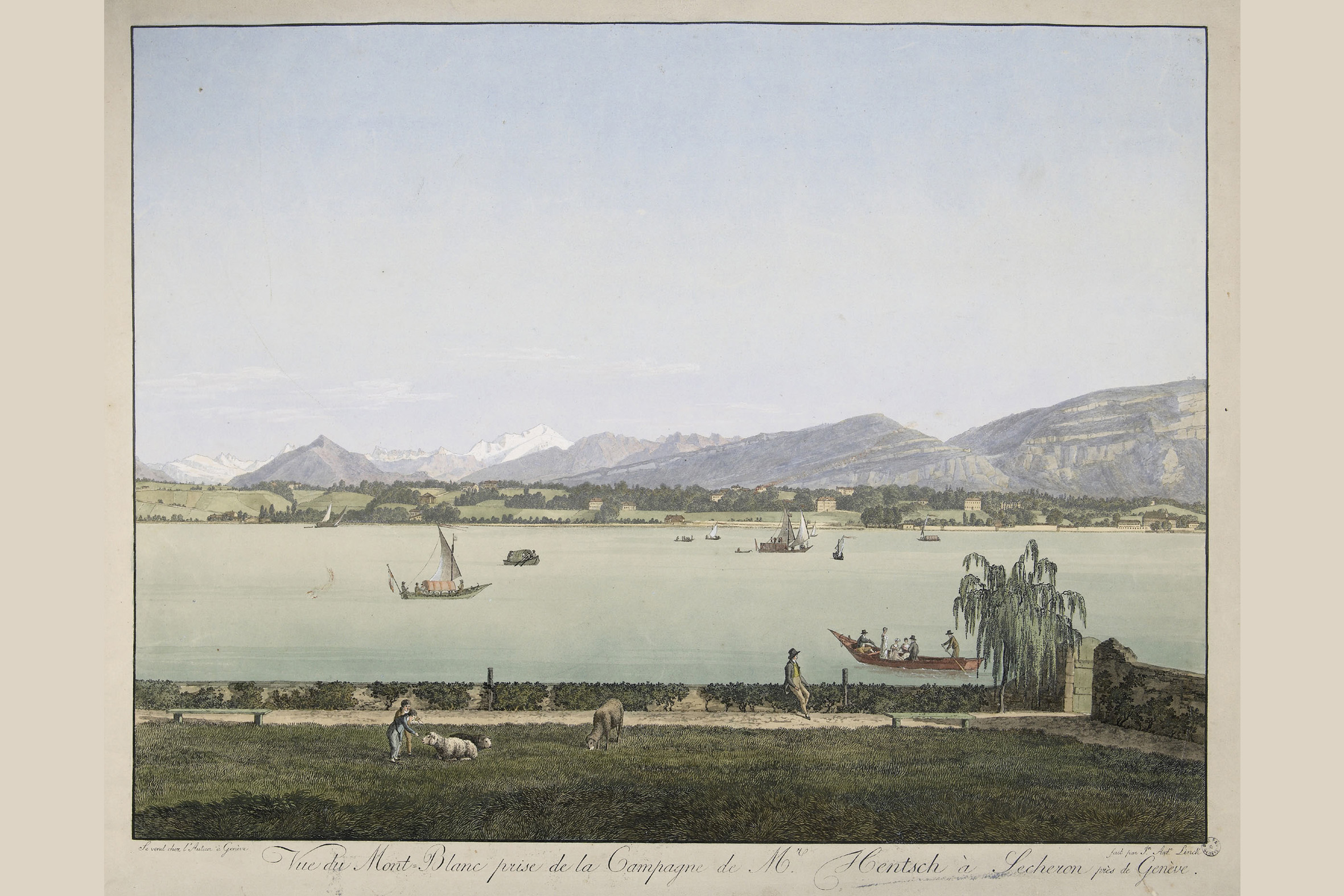

Colored print by Winterlin, L. Weber, Hasler et Cie éditeurs

© Bibliothèque de Genève

When it was announced that Geneva had been chosen to host the League of Nations, elevating the city “so to say to the rank of capital of the world,” as reported in the Tribune de Genève on 30 April 1919, the pride was immense, but the infrastructure absent. In practice, the city had little to recommend it for the role: no airport, barely a train station, and no buildings suitable to serve as offices or staff lodgings. It did have an opera, however, and a large concert hall, a theatre, and several grand hotels built during the Belle Epoque to complete the idyll sought by wealthy travellers eager to nurse their spleen in the birthplace of Rousseau. Acutely attuned to the needs of this emerging group, soon to be known as “tourists,” James Fazy and Henri-Guillaume Dufour, the masterminds of Geneva’s 19th-century modernization, created elegant embankments on either side of the beautiful body of water which graced the city’s image. Geneva in 1919 lacked the accoutrements of twentieth-century aspirations, but boasted natural treasures enhanced in the previous century: a reconstructed lakeside setting, dominated to the South by the epitome of savage beauty, Mont Blanc.

View on the lac and Mont Blanc from the Moynier and Bartholoni estates in the 1920s

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

One cannot possibly begin a history of international architecture in Geneva without linking it historically to the cultural emotions that placed the city on the map of the Grand Tour: what foreigners saw and loved, Genevans in turn saw and loved. The charm and beauty of the place, “discovered” by means of an aesthetic campaign launched in the eighteenth century by Horace Benedict de Saussure’s “conquest” of Mont Blanc, and fully put to profit in the nineteenth, became its heritage. Upon that heritage was the League of Nation to be implanted. The Genevans would have to share it with the internationals, in a complex relationship that combined conservation concerns with the needs of modernity.

The early built environment of international Geneva reveals a prudent yet rapid transition from an aesthetically minded bourgeois century to one in which function reigned. Office buildings were to replace charming old houses “in the most beautiful part of our beautiful canton,” the president of the Grand Council (the cantonal parliament) announced in May 1919, while inviting the deputies to extend a warm welcome to the League. “The prospects this opens up for us are both bright and heavy with responsibility,” he warned.

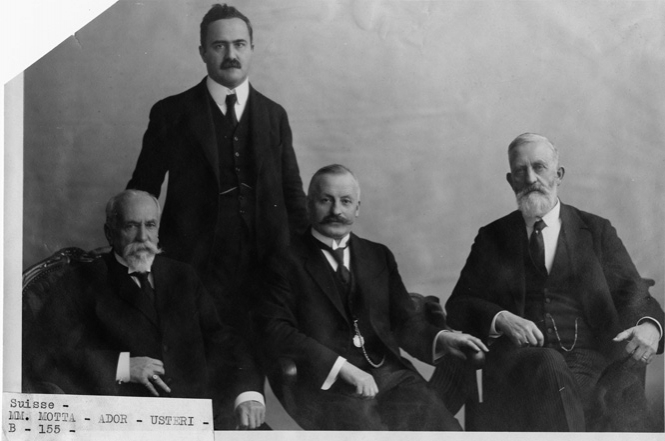

Delegation of Switzerland (Giuseppe Motta, Gustave Ador, and Paul Usteri) to the League of Nations, 1920

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

In the first few years of the League’s establishment in Geneva, a mild struggle within the leadership divided those who wanted the headquarters in Brussels and those who preferred, or acquiesced to, Geneva. Sensing the threat of a sudden about-face – Brussels, after all, was a wealthy and brilliant capital, the epitome of modernity – the Swiss and Genevan authorities played their winning card: the landscape. This context explains the two first founding gestures of what would later become the international quarter.

The first lay in the choice of the Hôtel National as the headquarters of the League Secretariat. The Secretary General, Sir Eric Drummond, and his deputy, Jean Monnet, made a first fact-finding trip to Geneva in August 1920. In June, they had received several offers from private landowners, some in the city centre or along Quai du Mont-Blanc, others on the left bank, near the Parc de la Grange, or in the Eaux-Vives. The League took note, but warned that its transfer to Geneva was still uncertain. When the time came, Drummond and Monnet selected none of the proposed plots. During their brief visit, they chose the Hôtel National, one of the city’s grandest, which was then closed for renovation. A luxurious building in the French classical style, it had been inaugurated in 1875 on land reclaimed from the lake at the time of the city’s remodelling, and stood on the “Quai du Mont-Blanc,” directly opposite the Hôtel Métropole on the left bank, across from the Jardin Anglais.

Legislative decree of the Grand Council of the Republic and Canton of Geneva, on 18 September 1920, for the purchase of the Hôtel National Geneva, for the League of Nations' headquarters.

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

The League put 5.5 million francs on the table. Property transfer tax amounted to 700,000 francs. As a gesture of goodwill, the Genevan government, or Council of State, opted to waive the tax and thus “offer more than platonic hospitality” to the League, as it explained to the Grand Council. The wording of the law that would make this gift legal was hotly debated. The left opposed it, citing the housing shortage and the poverty of the working class. Taxpayers should not have to pay for the League, they argued, decrying it as a “League of Capitalist Interests”. Nonetheless, a majority of the cantonal parliament supported the exception. “It is a noble gesture we are making,” one member opined. “Of course, we would prefer that no sacrifice be necessary, yet we make it willingly, joyously, because we know that we will reap the rewards a hundredfold, in the honour for Geneva of hosting the headquarters of the League of Nations.”(1)

The League Secretariat settled into the Hôtel National after several months of renovation. The move was temporary, but it completed the first act; the new institution, and any offices or staff quarters it would later need, would be situated on the right bank. Urban planning considerations played no part in the choice, which arose instead from opportunities latent in the beautiful Geneva of turn-of-the century tourism, a conclusion that was amply born out by the failure of an initial plan to locate the Palace of Nations in the Pâquis neighbourhood.

Hôtel National before 1905

© Bibliothèque de Genève

In the spring of 1923, the Swiss government, the canton, and the city jointly purchased the Armleder estate, south of the Hôtel National, intending to offer it to the League of Nations for the new buildings it urgently needed. Geneva’s town planners saw the opportunity to save a “poorly built” and “anarchic” neighbourhood, which was “unworthy of a city that aims to host the representatives of the whole world, as well as their institutions,” in the words of the architect Camille Martin.(2) But the jury of architects whom the League Council had commissioned to design a conference hall on that site soon deemed the Armleder plot unsuitable. The League didn’t see itself in town, dreaming instead of “parks, gardens, and views of the Alps, a romantic archetype of Switzerland that it would not have found on the fringes of a working-class district.”(3)

Its ambition was affirmed by a second founding gesture: the gift from the Swiss government to the International Labour Organization of the “Campagne Bloch,” a lakeside estate on the Sécheron promontory. The previous owner of this imposing villa, nestled among several large properties including Mon Repos, la Perle de Lac, and the Moynier, Bartholoni, and Barton estates, was Jules Bloch, a watchmaker from Neuchâtel who became a munitions manufacturer during the First World War and had neglected his tax obligations. The Federal government demanded payment, in place of which he handed over his property in Geneva, valued at a million francs. Thanks to this gift, the ILO became the first international organization to secure the sort of location that the League of Nations was intent on gaining to signify its prestige. The city centre was now out of the question.

In 1926, the League spent 2.7 million francs from its own purse to buy the Moynier and Bartholoni estates and the Perle du Lac, which was expropriated in the public interest. Spanning approximately five hectares, the latter exemplified early-twentieth century urban elegance: set on a rolling hill that plunged down to the lake, dotted with charming villas and hundred-year-old trees. The estate owed its name to Hans Wilsdorf, the founder of Rolex, who had bought the cottage from the Bartholoni family and, deeply moved by its beauty, reportedly exclaimed, “This is really the Pearl of the Lake!”

View of the Moynier and Bartholoni villas and la Perle du Lac in the 1920s

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Villa Lammermoor in the park Barton

© Bibliothèque de Genève

The Moynier, Batholoni, and Paccard families, who agreed to sell their land to support the grand designs of the League of Nations, had helped found the Red Cross and thus shared a history of internationalism. They belonged to an informal network of companies and political and cultural organizations that allowed Geneva’s influence to be felt far beyond its borders. A spontaneous affinity existed between these worldly Genevans and the world that was arriving to their city. The Council of State chose one of their number, the banker Guillaume Fatio, to act as intermediary between the canton and the League for all practical matters.

The planned Palace of Nations was not built on these former estates, as the plot was soon found to be too narrow. Nonetheless, throughout the competitions and controversies leading up to this decision, the site’s beauty left such a deep impression on everyone involved that it came to be seen as an inescapable ideal. This explains why the League set its sights on the enchanting Ariana estate — property of the city of Geneva — and the commanding tone with which it imposed its choice: if not the Ariana, please note that Vienna has made us offers! (5)

Geneva didn’t need to be told twice. The town council agreed to grant the League a building lease on a large portion of the Ariana, after lifting the testamentary dispositions of its last owner and donor, Gustave Revillod, in exchange for similar surface rights on the Moynier and Bartholoni estates.

What the League lost in lakeside appeal, it gained in stunning views. The Genevans, for their part, recovered public access to the land next to the lake, which they had thought lost forever after discovering the proposals submitted to the first architectural competition. In his plan for a “global city,” the visionary Belgian architect Paul Otlet captured the locals’ concerns: “What behemoths are these buildings now being planned, whose silhouettes will utterly dwarf the modest lake! No, no, no, the lake belongs to the people of Geneva, not to the League of Nations. To build is to choose architects, styles, and scales. And a city must seek to connect its past and its future. Hence, the harmony of a city, of an urban setting, must never be destroyed, and the last word, the moral decision at least, should be left to the guardians of the City.”(6)

Otlet then responded to this objection from the League’s point of view: “That cannot be: we are the world and we have come to you. You must build and live on our scale. Geneva must rise to the level of the world, not the world descend to that of the city. The style shall be ours: either super classic, to rival Rome and Paris, since we contain within us both Italy and France; or super modern, since we embody a modern, novel, unprecedented idea. But Saint-Pierre Cathedral, the Taconnerie, or the the Escalade festivities are not our concern.” (7)

The refined Geneva of parks and gardens, which had dictated local tastes and charmed visitors, would have to transform itself into an international Geneva, as practical as it was functional. A need for functionality was therefore added to the requirements of beauty and eminence. The decision to build on the relatively isolated Ariana estate, outside the city centre, demanded more than ever a broad urban vision to plan new access roads and organize traffic. A group of concerned citizens, calling themselves “pour la Grande Genève” (for Greater Geneva), petitioned the Council of State to draw up a “complete and detailed development plan for the entire sector.” One of its members, the local architect Camille Martin, bluntly stated the problem: “The city, not as a spectacle for the eye, not as a stage set, but as an instrument for economic and social life, a tool designed to serve human needs. To improve the efficiency of this tool, adapt it to its new purpose, lower its cost: these are the ultimate objectives.”(8)

The time for expounding on the city’s beauty had ended; its job was done. It was time to take action.

League of Nations First Assembly, Geneva, 1920

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

The following articles explain how these goals were progressively achieved, or redefined, and how architecture sought to serve them.

(1) MGC, 18 September 1920

(2) Camille Martin, Pour la Grande Genève, 1927

(3) Alain Léveillé, Genève, capitale du monde, formation et transformation du secteur des organizations internationales à Genève, study commissioned by the Real Estate Department of the City of Geneva from the Centre de recherche sur la rénovation urbaine (CRR) of the School of Architecture, University of Geneva, June 1980.

(5) League of Nations’ “Committee of Five” (architects), note to the Geneva authorities, September 1928

(6) Paul Otlet, in La Cité mondiale, Geneva World Civic Center Mundaneum, p. 17

(7) Ibid., p. 18

(8) Quoted by Sylvain Malfroy in Matière,“Manières de pensée la grandeur, Genève et l’expérience de la mondialization dans les années vingt et trente”, Matières, n. 4/2000, vol. 4