Chapter 3: The William Rappard Centre: From a tree's perspective

The building that currently houses the World Trade Organisation (WTO) marked Geneva’s entry into the brave new era of international civil service. Commissioned in 1922, after the International Labour Organisation (ILO) chose to establish itself in Geneva, the building served as a testing ground for negotiations between the architectural requirements of an international agency and the sensitivities of its local hosts. Both parties – on the one hand, an organization representing the nations of the world and, on the other, a government representing its citizens – had an interest in reaching an agreement. Simple in theory, since the ILO leaders liked Geneva and Geneva was proud to have been chosen, but difficult in practice. This first experience established a precedent for handling all future disagreements between the internationals and the locals. Battered by aesthetic passions from all sides, the shores of the lake caused many a lively debate and stubborn quarrel over the years. Their old sequoias still laugh at the memory of all they have seen and heard.

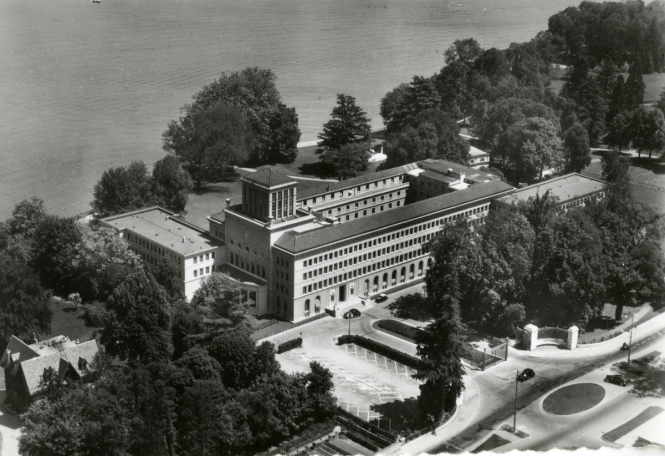

The ILO building with its 1937 extentions

© Bibliothèque de Genève

Those stately trees – along with their neighbours, giant cedars and common species alike – featured prominently in the brief for the architectural competition of 1922, which directed applicants to “conserve, as much as possible, existing stands of trees, especially near the lake”. Declared the winner among 68 contestants, Georges Epitaux, an architect from the canton of Vaud, applied the suggestion to the letter. In fact, the federal government had made this criterion part of its conditions for transferring the splendid lakeside plot to the ILO. To secure local support for the city’s new international role, both Bern and Geneva wished to ensure continued public access to a favourite lakeside walkway. In a brochure celebrating the building’s inauguration, in 1926, the author and poet Paul Budry echoed their aims: “The trees and the shore remain. The play is being performed behind closed curtains, so to speak.”

The “actors” were 500 employees, and their stage was a building worth three million Swiss francs, offering “the dignity befitting an international institution”. Faced with the challenge of designing his first office building, Epitaux reached a compromise that reconciled the organization’s functional needs with the conservative taste of the time. Trained in the French Beaux-Arts tradition, like most architects in French-speaking Switzerland at the time, Epitaux delivered a five-storey-high quadrilateral in a neoclassical style, with an inner courtyard, a decorative cornice all around it and a roof lantern on top. The façades presented a regular grid of close-set, narrow windows, an utterly new style in Geneva.

Hall from the origal building transformed by Group8 architects

© WTO

The building’s lack of charm shocked traditionalists. Modernists decried it as overly academic. Budry, however, praised it: He argued that the grand ideal of peace and respect for the dignity of work deserved better than the “amiable nostalgia” of those pining for parks straight out of a Watteau painting. This building embodied rigour, restraint, and economy of means. “If work is to be regenerated through the law of standards, should not the ILO set an example?”, he wrote. The architect had written into stone “the political equality of individuals, without which there can be no solid unity”. The regularity of the façades was a sort of manifesto: “Standing before them, no one may say: here are the powerful, here the weak […] There is no ledge that says: me. No ornaments, no projections, nothing that implies pride or bombast.”(1)

The ILO, Geneva, and Bern managed to agree on everything, including the need to find funding for a new sewer, imposed by the canton’s Hygiene Committee after construction began yet omitted from the initial budget. This incident revealed the existence of a faction in Geneva willing to denounce the internationals as poisoners. It also revealed both the ILO’s lack of resources and the weakness of Geneva’s finances: the canton’s coffers were empty, and the political opposition was turning increasingly hostile. However, the ILO building was finished. Member states helped decorate it by donating sculptures, furniture, rugs, murals, and rare trees.

The new building by German architect Jens Wittfoht inaugurated in 2013

© WTO

By 1937, the building was already too small. Two extensions were added; the outside wing was raised. The original quadrilateral was extended with a second identical building, also enclosing an inner courtyard. There was still not enough space, and the complex was growing increasingly lopsided.

In 1962, needing space for its new Institute of Labour Studies, the ILO changed strategies. It asked the Swiss government for help securing the “best architect available” in Switzerland to design a new concept.(2) Jean Tschumi, and later Eugène Beaudoin, drew up plans that daringly broke with the past. Local officials found their proposals interesting, but worried about public opinion, which would certainly reject them due to their height or the way they encroached on the lake. The sequoias trembled to the tips of their branches. Some say the hornbeams along the lakeshore walk cried.

The motto was lightness and transparency

© WTO

The trees eased up only once the ILO decided to abandon the lake, rather than face a referendum. The organization moved in 1975, as soon as its new headquarters in Grand Morillon were ready. Three other institutions immediately took over Epitaux’s building and its annexes: the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the library of the Graduate Institute of International Studies. This disparate trio coexisted as amicably as possible for two decades, until the GATT became the World Trade Organization (WTO). After a heated international bidding war to host its headquarters, Switzerland’s entry on behalf of Geneva was declared the winner.

The jewel in Switzerland’s generous and politically committed offer was the building by the lake, surrounded by hundred-year-old trees and with a stunning view of Mont Blanc. The Swiss government offered the WTO a rent-free, 99-year lease and agreed to renovate the building at its own expense. A large conference hall and a car park were promised within three years.

Upon moving into the former ILO headquarters in 1975, the GATT renamed the building the William Rappard Centre, after the famous Genevan to whom the city owes its present international role. The director at the time, aiming to distinguish the GATT from the building’s previous owner, had all the paintings and murals celebrating the dignity of work either removed or covered over, assuming they would not suit his delegates’ taste.

Offering the trees a mirror as a tribute

© WTO

In 1995, the newly created WTO thus moved into a series of renovated but bland offices, which retained none of the original building’s cachet. A 710-seat conference room, built in a corner of the drive leading to the entrance, was inaugurated in 1998. The architect Ugo Brunoni, a Ticino native, made the most of every available square metre by building up to the Rue de Lausanne and insulating the amphitheatre with a soundproof wall. This solution, though elegant, reflected the space constraints that now plagued the WTO, like the ILO before it.

The organization was quick to sound the alarm. Based on its agreement with the Swiss government, the WTO argued that it needed more space to enable it to admit new members and meet its growing responsibilities. It felt all the more justified in making these demands as the promised car park had not yet materialized. In 2003, the Building Foundation for International Organizations (BFIO) announced a competition for a new annex on Avenue de France, 800 metres from the Rappard Centre. By 2005, building plans had been completed and the necessary permissions obtained, the partners had reached an agreement, and funding had been secured through an interest-free 60 million Swiss franc loan. Construction was about to begin when the WTO chose a new director.

"La Dignité au Travail" mural fresco by Maurice Denis given to ILO in 1931 by the International Confederation of Christian Trade Unions

© WTO

Pascal Lamy was a former French finance ministry official and member of Jacques Delors’s cabinet in Brussels. He understood how the international civil service worked, and insisted that splitting the organization’s tasks between two locations was a waste of time and money. He wanted a single site.

The sequoias in Parc Barton anxiously observed the mounting tension: what fate awaited them?

The WTO did not understand the Swiss hesitation; the Swiss, in turn, resented Lamy’s stubbornness. Rumours of the WTO’s imminent departure began to fly. Though it was not the first time, Switzerland was worried nonetheless. The government searched for a site, but found none. The year 2007 thus saw the resurgence of a forbidden idea: the terrifying notion of extending the Rappard Centre in its current location. It was the cheapest solution, and Switzerland was prepared to contribute 130 million francs.

The proposed extension would be erected on the southwest car park, an expanse of concrete shaded by a row of broad-leaved trees, separating the plot from the sequoias of Parc Barton. Suddenly panic-stricken, the ancient redwoods took the stage and claimed a leading role. In the botanical Geneva of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, trees have a cunning way of obscuring the view of the forest – the forest of political intentions, that is. The far left enlisted them in their campaign, which sought to rally park-lovers to quash the project. Their true target, however, was the WTO.

Realizing that the WTO’s image was less than stellar in Geneva, Pascal Lamy resolved to change it by opening up the organization. He re-established the forgotten connection between trade and work by restoring the artistic heritage of the former ILO building, which the GATT had obscured. Murals offered by American, French, Spanish, and Dutch trade unions in the 1930s were restored, returned to their original location, and unveiled to the public, who made no secret of their delight. A model of the future annex was presented: enveloped in glass, it showed no intention of “annihilating the Perle du Lac park”, as opponents claimed.

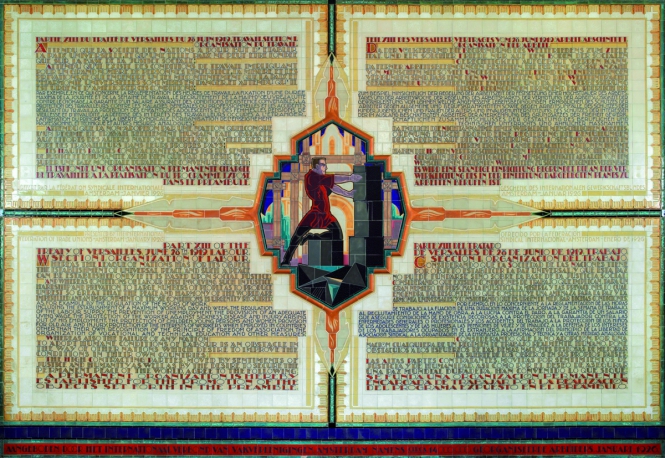

Delft Ceramic Panel by Albert Hahn Jr. A reproduction in four languages of the part of the Versailles treaty which became ILO's Constitution. Gift from the International Confederation Trade Unions based in Amsterdam

© WTO

In September 2009, by a majority of 62 per cent, the Genevans approved the extension of the WTO on its existing site. The sequoias could rest easy: the crystalline façade of the future annex would mirror their distinguished presence for all to see.

Inaugurated in June 2013, the annex was designed by German architect Jens Wittfoht, following an international competition that attracted 120 proposals from 25 countries. Ambitious in its modesty, this architectural oxymoron makes four floors of offices go almost unnoticed — by using the transparency of glass with remarkable technical and aesthetic mastery. Wittfoht made no concessions to the principle of discretion. Even the colours of the interior, visible from the outside, were chosen to harmonize with the overall structure’s subdued nature.

The annex is located to the south of the Epitaux building, which it references by reflecting its image. Like a theatre with no backstage, it comprises open-plan offices for 300 employees, 10 meeting rooms, a printing facility, and a kitchen with a 250-seat restaurant. The underground parking has a capacity of 200 cars and 50 bicycles. The energy-efficient design complies with the Minergie-P standard, thanks to double-layer glass façades and heat pumps drawing energy from the lake’s lower layers.

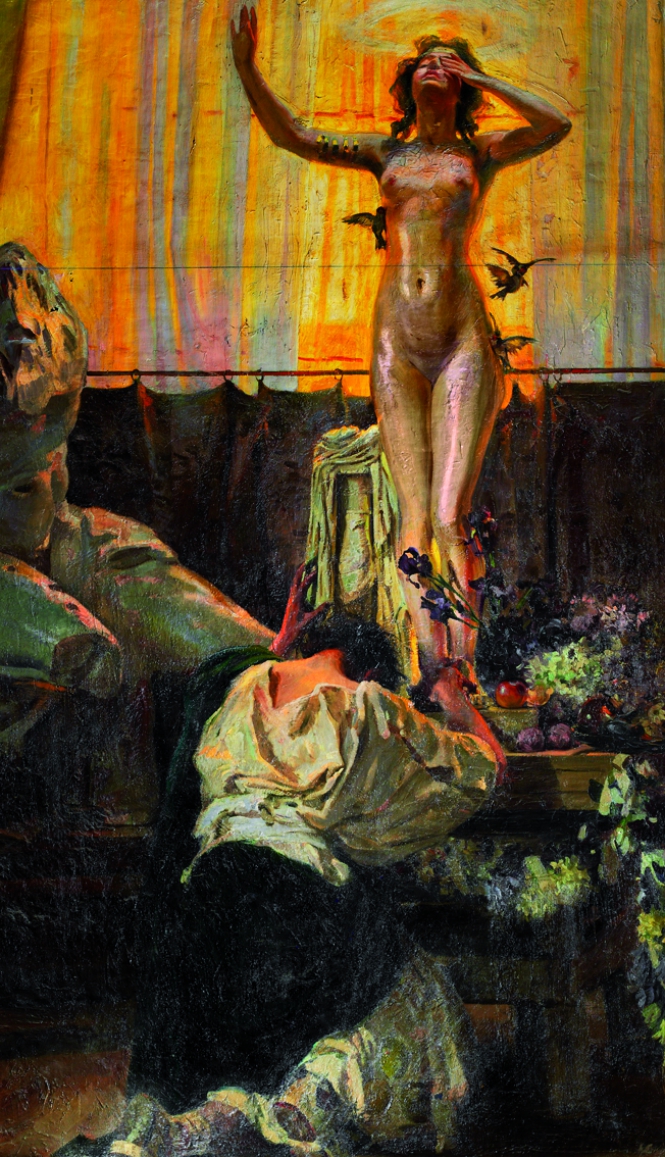

"Pygmalion" painted by Eduardo Chicharro y Agüerra (1873 - 1949). Given by the Spanish government to ILO in 1925

© WTO

Meanwhile, the original building was renovated, and space usage optimized.(3) The commission was awarded to the two architects responsible for the initially proposed annex on the Avenue de France: François de Marignac and Oscar Frisk of the Geneva practice Group8. Their brief was to modernize the building while preserving its spirit. They rethought the layout entirely, turning the long-abandoned central courtyard into the building’s social heart. The addition of a skylight – a triumph of thermal engineering – transformed it into a bright atrium that invites lingering in conversation at the foot of an imposing strangler fig. After being closed for years due to security concerns, the podium facing the lake was restored to its original function as a terrace through an ingenious trick: lowering the level of the public walkway in front of the security wall made the latter too high to climb, enabling it to shed its fortified look.

Today, WTO staff and local residents alike can enjoy their respective parts of the park on either side of a wall that seems to apologize for its existence. The old sequoias are still standing. In 2015, they were joined by 15 youngsters, planted alongside the pedunculate oak and the Arizona cypress to one day succeed their elders and bear witness to the events of the next hundred years.

One of the two giant Cedars which commands the destinity of the site

© WTO

(1) Paul Budry (dir), L’édifice du Bureau international du Travail à Genève, 31 August 1926.

(2) Quoted by Franz Graf and Giulia Marino in “Siège de l’OIT à Genève”, Laboratoire des Techniques et de la Sauvegarde de l’Architecture, EPFL, June 2014.

(3) Information about the annex and the renovation of the old building comes from conversations with Victor do Prado, a member of Pascal Lamy’s cabinet who supervised all of the building and renovation work.