Chapter 9: The International Labour Organization: The bell tower of International Geneva

In a brochure presenting the new headquarters of the International Labour Organization (ILO), Alberto Camenzind, one of its three architects, explained that the urban landscape of his native Ticino is defined by its church steeples. Perched on a hill in the Morillons neighbourhood, the ILO would one day stand as “one of Geneva’s defining structures”, he added.(1) He was right. Viewed from the left bank of the lake, the cityscape today is dominated on one side by Saint-Pierre Cathedral and on the other by the ILO: a bell tower without a bell, exerting its dominance from a horizontal position.

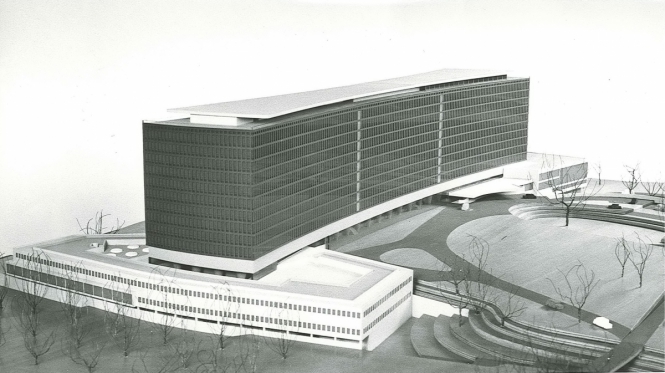

The final model of the building, put one hand on the library and the other on the cafeteria

© ILO Archives

When it opened in 1974, the ILO was the largest administrative building in Switzerland. A biconcave rectangular block, it stands 11 floors and 50 metres high, 190 metres long, and 32 metres wide at its widest point. It boasts a volume of 555,000 cubic metres –– equivalent to 1,100 superimposed single-family homes –– with 4,500 windows, 1,250 offices housing 2,000 employees, and 12 meeting rooms with a total of 1,400 seats. The colossus gobbled up 90,000 cubic metres of concrete, or 22,500 10-ton trucks’ worth, and 11,700 tons of steel — 4,000 times more than the Eiffel Tower (2).

The biggest construction site in Switzerland at the time and one of the largest in Europe

© ILO Archives

The first conference, in 1921, at the casino, on the site of the current Hotel Kempinski

© ILO Archives

The building’s prominence was equal to that of the International Labour Organization (ILO) itself. Many new nation-states created by decolonization had joined the ILO in the post-war years. International labour standards, negotiated jointly by governments, employers, and employees, had multiplied. This tripartite process, unique to the ILO, drew a growing number of experts and representatives of governments, trade unions, and employers’ organizations to Geneva. The organization had outgrown its original headquarters, built next to the lake in 1926, despite the addition of several annexes in the 1930s and 1950s. In the early-1960s, the ILO asked the architect Jean Tschumi to design a further extension, but his sudden death cut the project short. His replacement, Eugène Beaudoin, proposed extending over the lake; the Journal de Genève objected that this move would “disfigure a site to which the Genevans are very much attached” (3).

Swiss officials did not want to risk confrontation with the local population. Motivated by political prudence, and eager to avoid alienating Geneva’s international organizations, the Swiss government offered to move the ILO’s entire operations to a new site in Grand Morillon, on the hillside overlooking the lake, which — at more than 10 hectares — was three times larger than its existing plot on the Rue de Lausanne.

Leaving its historical home was difficult for the ILO. It had grown as attached to the lake as the Genevans. But the offer was not an easy one to refuse. In a meeting with representatives of the Swiss government in late-December 1964, the ILO’s directors acknowledged the advantages of moving to a plot earmarked for international organizations, which could be extended to meet future needs and imposed few architectural constraints aside from a strict height limit, due to the nearby airport (4).

The move was structured as a swap: in exchange for the 11.5 hectares in Grand Morillon, the ILO gave the Canton of Geneva its 3.35-hectare site next to the lake, along with buildings valued at between 17 and 20 million Swiss francs. The remaining funds for the new headquarters came from a 40-year, preferential-rate loan from the Building Foundation for International Organizations.

Now that this tough decision had been made, the ILO was in a rush to start. Rejecting the competition route as overly burdensome, the organization commissioned Eugène Beaudouin to adapt his volumetric studies and floor plans for the previous project to this new location.

Beaudouin was an important figure at the time. A winner of the prestigious Grand Prix de Rome, he had served as director of the Ecole d’architecture de Genève since its founding in 1942, while also holding positions as chief governmental architect for the Paris area and professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Paris, and leading the renovation of the port of Marseilles. He had achieved fame in the 1930s for several avant-garde civic projects built in partnership with Marcel Lods: the Chant-des-Oiseaux housing estate in Bagneux, an open-air school in Suresnes, and La Muette housing estate in Drancy (which the Vichy government had turned into an internment camp for Parisian Jews). He was among the architects shortlisted for the UNESCO headquarters in 1952, but the advisory board, which included Gropius, Saarinen, and Le Corbusier, had rejected his proposal.

The architects Eugène Beaudouin, Pier Luigi Nervi et Alberto Camenzind

© ILO Archives

In Geneva, his institutional standing enabled him to play a significant role in shaping the appearance of the right bank, whether as a member of competition juries or as an advisor to new public housing estates. His charisma and closeness to those in power greatly benefited his current and former students (5). Geneva was in the midst of a “Beaudouin moment”.

The ILO chose two other architects of “established reputation”(6) to help Beaudoin plan and execute its new headquarters. Alberto Camenzind, a Ticino native, was acclaimed for his efficient management of the National Exhibition in Lausanne in 1964. The Italian engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, the inventor of ferro-concrete, was celebrated for remarkable feats of engineering, including the UNESCO headquarters, in partnership with Marcel Breuer and Bernard Zerhfuss, and the spectacular concrete columns of the ILO Technical Training Centre in Turin.

Beaudoin, Nervi, and Camenzind’s creation was up against three landmark buildings designed for the United Nations over the previous decade: the UN headquarters in New York, UNESCO in Paris, and the WHO in Geneva. Within the small world of star architects and their institutional patrons, these three structures set an example to follow, combining symbolic impact with user-friendly qualities. The memory lingered of Eero Saarinen’s ravishing design for the WHO, an object of desire which took second prize but was never built What all these buildings had in common was gigantic size. Hence, the ILO would be large.

To ensure that the building’s reputation matched its magnitude, the ILO’s board of directors created an “Advisory Committee of internationally known architects”, tasked with overseeing the project and advising the director-general. Its members included Wallace Harrison, head architect of the UN headquarters in New York; Carlos Raul Villanueva, who designed the University City of Caracas; and Robert H. Matthew, founder of the Edinburgh School of Architecture, an institution often compared to Gropius’s Bauhaus.

The Advisory Committee of architects, from left to right H. Matthew, Marian Sulinowski, Carlos Raul Villanueva, Wallace Harrison and State Counselor of the Canton of Geneva, François Peyrot

© ILO Archives

Bolstered by this illustrious pedigree, the new “Palace of Labour” would certainly achieve landmark status. Its monumental size was understood to symbolize the organization’s objective of a “fairer and freer society” (7). The grey skies of the Cold War years saw the emergence of several other emblematic buildings, including the Berlaymont in Brussels, headquarters of the European Commission, with a volume of 873,000 cubic metres over 13 floors, and the Moscow headquarters of Comecon, the Soviet commercial union, with a volume of 400,000 cubic metres and 30 floors.

The architectural team finalized their calculations and blueprints, and the first stone was laid on 28 May 1970. The structure that gradually arose was a south-facing slab, abutted by two lower buildings to the north and south, the former containing service areas, and the latter several meeting rooms and a library. A four-level underground parking garage completed the complex.

The building’s silhouette, designed by Beaudouin, recalls Saarinen’s project for the WHO. The load-bearing structure, devised by Nervi, is an extraordinary technical achievement: a series of cross-shaped pillars supports the central portico and opens up a long, stately walkway on either side, offering views of the grounds through its glassed-in façade. This atrium functions as the “centrepiece of the complex”, according to a heritage study by the architects Franz Graf and Giulia Marino of the Federal Polytechnic Institute of Lausanne; it garnered high praise when the building was inaugurated in November 1974.

The "Pas-Perdus" lobby

© DR

The columns so delicately attached to the ceiling

© DR

The large side corridor

© DR

The Board room entrance hall

© DR

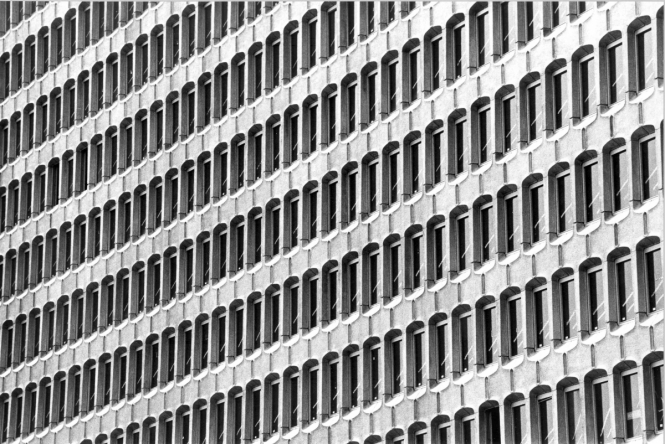

The sheer size of the main building’s façade posed a challenge: which material could be used to elegantly cover the water pipes and air ducts running along the outside of the structure, while highlighting its curved shape? The solution lay in Camenzind’s rolodex (8). The architect knew a company in Schaffhausen, Georg Fischer, which made shaped panels of cast aluminium known as Alcast, using a process developed in Japan. These panels could be used to add thickness to the curtain-walls of contemporary architecture. This technology provided the 190-metre-long façade with its characteristic cladding of relatively small, uniform 1.2-metre-wide panels, which wrap the building in a tight net of aluminium, creating a repetitive pattern that serves as decoration. The design of the façade set the tempo of the building’s inner life: basic staff offices are two modules wide, increasing to three, four, or five depending on the occupant’s position in the institutional hierarchy.

© ILO Archives

A detail of the ILO's facade (left) next to the WHO

© DR

The Swiss landscape architect Walter Brugger, who had extensive experience with similar sites, helped mitigate the impact of such a massive building on the already majestic location of the Grand Morillon. He cushioned the south side of building with an artificial hill and added a pond to the west, but left the east façade free. He judiciously chose trees and bushes to act as an ever-changing, colourful chorus, moderating the severity of the central protagonist.

One of the statues of the park, "The triumph of work". Gift from the Government of India

© DR

The ILO is a product of its time: a triumphant creation of progressive thought, certain of its ability to improve the human condition. Its size reflects the ambition it represents. That was how its users saw it: “a responsibility towards the world”, in the words of a former director. Outsiders were often less enthused. In a vitriolic 1974 review, the architectural critic Henri Stierlin dismissed the ILO headquarters as the “last of the dinosaurs”, accusing it of “visual terror” and ruthlessly listing its many flaws (9). Today, however, the authors of the above-quoted heritage study rate it as a building of “exceptional value” — though its critics may consider it a dinosaur, it satisfied all of its expectations.

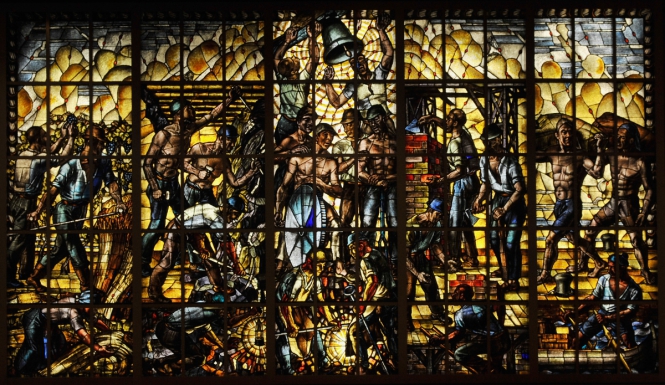

75 stained-glass windows depicting the work of the German Expressionist painter Max Pechstein, and the famous glass makers Puhl, Wagner and Heinersdorf. Gift from the Federal Republic of Germany

© ILO Archives

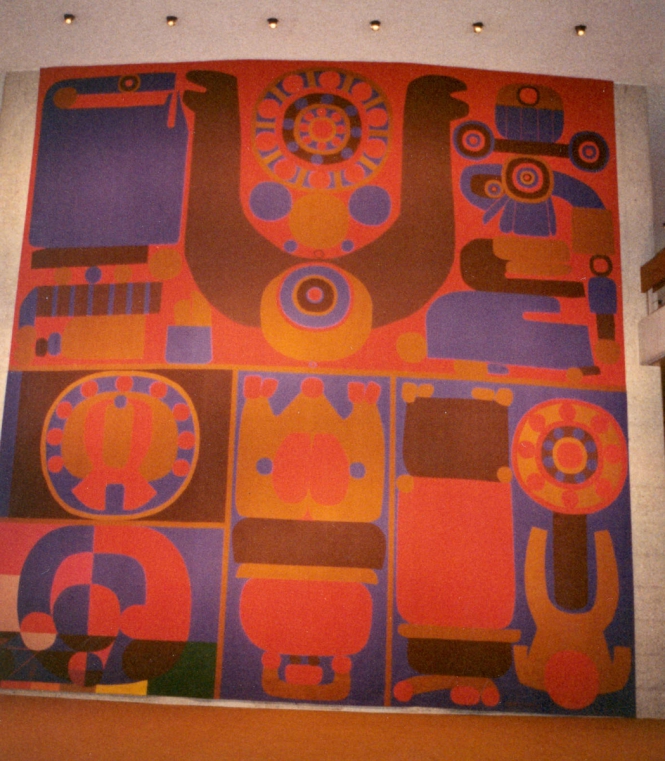

"Le rouge au front", Gobelins tapestry (110m2), painted on cardboard and engraved by Pierre Courtin (1921-2012). Gift from France

© Marcel Crozet/BIT

(1) Quoted by Franz Graf and Giulia Marino in their heritage study, Siège de l’OIT à Genève, Laboratoire des Techniques et de la Sauvegarde de l’Architecture, EPFL, June 2014, p. 63

(2) ILO, Department of Facilities Management

(3) Journal de Genève, 24 May 1963

(4) According to the minutes of the meeting, summarized by Graf and Marino, op. cit., p. 29

(5) Isabelle Charolais, Bruno Marchand, and Michel Nemec, “Genève: l’urbanisation de la rive droite et le rôle d’Eugène Beaudouin”, in Ingénieurs et architectes suisses, 1993, issue 15/16, vol. 119

(6) “Report of the Building Committee to the Governing Body of the ILO”, November 1965, quoted by Graf and Marino, op. cit., p. XX

(7) “Speech by the director of the Governing Body of the ILO at the ground-breaking ceremony”, quoted by Graf and Marino, op. cit. p. XX

(8) Graf and Marino, op. cit., p XX

(9) Journal de Genève, 30 November 1974, and Werk, n.7/1974